Soyuz 1: Falling to Earth

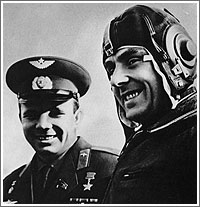

The Russian Soyuz program is the longest-running spaceflight program — variations of the spacecraft have flown consistently since 1966. It isn’t perfect; big technologies like spacecraft rarely are. There have been problems on recent missions where spacecraft have made hard landings. But overall its considered the safest and most reliable vehicle. But Soyuz hasn’t always been a reliable workhorse. The program got off to a very rocky start when the first mission, Soyuz 1, saw the launch of a fatally flawed spacecraft in 1966. (Left, the Soyuz 1 crew. Backup pilot Yuri Gagarin and prime pilot Vladimir Komarov. Source: The Russian Space Web.)

The Russian Soyuz program is the longest-running spaceflight program — variations of the spacecraft have flown consistently since 1966. It isn’t perfect; big technologies like spacecraft rarely are. There have been problems on recent missions where spacecraft have made hard landings. But overall its considered the safest and most reliable vehicle. But Soyuz hasn’t always been a reliable workhorse. The program got off to a very rocky start when the first mission, Soyuz 1, saw the launch of a fatally flawed spacecraft in 1966. (Left, the Soyuz 1 crew. Backup pilot Yuri Gagarin and prime pilot Vladimir Komarov. Source: The Russian Space Web.)

The First Soviet Spacecraft — Vostok and Voskhod

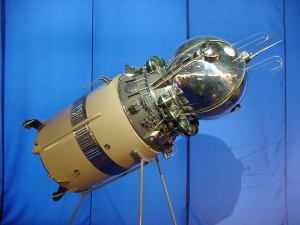

Yuri Gagarin became the first human to orbit the Earth on April 12, 1961, in theVostok spacecraft. It was rudimentary like it’s American counterpart the Mercury capsule. One cosmonaut could fit inside the spherical craft wearing a spacesuit. Small thruster rockets gave the cosmonaut control over his attitude in orbit, but like Mercury this was all the control he had. To land, Vostok used on a single parachute to slow its descent; there was no soft-landing system. The pilot ejected in the final stage of his descent and reached the ground by his own parachute. (Right, the Vostok spacecraft. The round module is the descent module.)

Yuri Gagarin became the first human to orbit the Earth on April 12, 1961, in theVostok spacecraft. It was rudimentary like it’s American counterpart the Mercury capsule. One cosmonaut could fit inside the spherical craft wearing a spacesuit. Small thruster rockets gave the cosmonaut control over his attitude in orbit, but like Mercury this was all the control he had. To land, Vostok used on a single parachute to slow its descent; there was no soft-landing system. The pilot ejected in the final stage of his descent and reached the ground by his own parachute. (Right, the Vostok spacecraft. The round module is the descent module.) The second generation spacecraft, Voskhod, was a modified Vostok that had some significant improvements over its predecessor. It was the first spacecraft capable of carrying a multi-person crew to orbit providing they weren’t wearing spacesuits. But it shared some of Vostok’s limitations. It was spacious, but couldn’t manoeuvre in orbit at all. (Left, Voskhod. Source: RKK Energia.)

The second generation spacecraft, Voskhod, was a modified Vostok that had some significant improvements over its predecessor. It was the first spacecraft capable of carrying a multi-person crew to orbit providing they weren’t wearing spacesuits. But it shared some of Vostok’s limitations. It was spacious, but couldn’t manoeuvre in orbit at all. (Left, Voskhod. Source: RKK Energia.)

Soyuz

To get closer to the goal of a Soviet landing on the Moon and to match the American accomplishments of the Gemini program, the Soviet space program developed the Soyuz spacecraft in the early 1960s.

The three-man Soyuz spacecraft was a significant improvement over Voskhod, designed to eventually take cosmonauts to the Moon. It could actively manoeuvre in orbit for rendezvous and docking, a necessary ability for circumlunar flights and eventual surface exploration. The lunar exploration plan developed by Chief Designer Sergei Korolev was similar to Apollo — a mothership and a lander would separate in lunar orbit, the latter descending to the surface while the former waited in orbit. (Right, Soyuz in orbit during the Apollo Soyuz Test Project. 1975.)

The three-man Soyuz spacecraft was a significant improvement over Voskhod, designed to eventually take cosmonauts to the Moon. It could actively manoeuvre in orbit for rendezvous and docking, a necessary ability for circumlunar flights and eventual surface exploration. The lunar exploration plan developed by Chief Designer Sergei Korolev was similar to Apollo — a mothership and a lander would separate in lunar orbit, the latter descending to the surface while the former waited in orbit. (Right, Soyuz in orbit during the Apollo Soyuz Test Project. 1975.)

To reenter the atmosphere, a descent module would separate from the instrument module and return alone (like the Apollo Command Module). Unlike Vostok and Voskhod, Soyuz had a flat bottom which gave it a limited amount of aerodynamic lift. A large parachute would slow its initial descent, and feet above the ground retrorockets would fire to provide the crew inside with a soft landing. It was the first time cosmonauts would stay inside their spacecraft during landing.

An early, non-lunar bound version of the spacecraft was developed for testing and training in Earth orbit. The 7K-OK model would go through the Soviet equivalent of the Gemini program, working out the kinks from rendezvous and docking manoeuvres.

An early, non-lunar bound version of the spacecraft was developed for testing and training in Earth orbit. The 7K-OK model would go through the Soviet equivalent of the Gemini program, working out the kinks from rendezvous and docking manoeuvres.

But a lot of things changed in the Soviet space program while Soyuz was undergoing development. In 1964, Leonid Brezhnev organized a successful coup over Nikita Khrushchev and took control of the country. In terms of space, he was as demanding as his predecessor, pushing for launches to coincide with important dates or events. Mission launches were often planned as part of a larger national ceremony. (The descent module of a more modern Soyuz, Soyuz TM 10 that landed in 1990. The flat bottom is clearly visible.)

The Soviet space program was dealt a major blow two years later when Korolev died suddenly from complications during surgery. His successor, Vasiliy Mishin, was under the same political pressures to launch on certain dates, but he had to do this without Korolev’s expertise.

The Mission Plan

As preparations began for the first Soyuz flight, details of the mission were kept tightly under wraps. It wasn’t until April 20, 1967 that the prime and backup pilots were confirmed — Vladimir Komarov and Yuri Gagarin respectively — and the launch date was set for April 23. (From left to right, rocket engineer Vasily Mishin, mathematician Mstislav Keldysh, physicist Igor Kurchatov, and rocket engineer Sergey Korolev. Source: Ria Novosti/Science Photo Library.)

As preparations began for the first Soyuz flight, details of the mission were kept tightly under wraps. It wasn’t until April 20, 1967 that the prime and backup pilots were confirmed — Vladimir Komarov and Yuri Gagarin respectively — and the launch date was set for April 23. (From left to right, rocket engineer Vasily Mishin, mathematician Mstislav Keldysh, physicist Igor Kurchatov, and rocket engineer Sergey Korolev. Source: Ria Novosti/Science Photo Library.)

Launch day was celebrated with a sparse press release saying only that Soyuz 1 was simply the first mission in a new program. But shrewd observers noticed that the mission had a numeric designation, uncommon for the first mission in any program. In both the Vostok and Voskhod programs, mission had a numeric designation staring with the second flight. Reporters and observing parties suspected there was a secret plan to launch a second Soyuz at the same time, and they were nearly right.

The flight plan for Soyuz 1 was complicated and risky. Komarov would launch on April 23. The following morning, Valery Bykovsky, Aleksei Yeliseev, and Yevgeny Khrunov would launch in Soyuz 2. Komarov’s was the more sophisticated spacecraft so he would manoeuvre Soyuz 1 to a rendezvous and docking with Soyuz 2. Once docked, two cosmonauts would don spacesuits and transfer from Soyuz 2 to Soyuz 1 by spacewalk. The restructured crews would land in their new spacecraft.

The flight plan for Soyuz 1 was complicated and risky. Komarov would launch on April 23. The following morning, Valery Bykovsky, Aleksei Yeliseev, and Yevgeny Khrunov would launch in Soyuz 2. Komarov’s was the more sophisticated spacecraft so he would manoeuvre Soyuz 1 to a rendezvous and docking with Soyuz 2. Once docked, two cosmonauts would don spacesuits and transfer from Soyuz 2 to Soyuz 1 by spacewalk. The restructured crews would land in their new spacecraft.

Before the Launch

The daring flight plan was more than Soyuz could really handle; many engineers and cosmonauts working towards the mission had doubts about its safety. Unmanned test flights revealed serious problems or else experienced failures that would have killed a human pilot.

Some engineers wanted to play it safe and continue with unmanned testing until all the bugs were worked out, but more unmanned testing lengthened the time since the last manned flight, and Brezhnev wanted to get Soviets back in space. The leader chose a date close to May 1 so the mission would coincide with the National Day of Worker Solidarity. A return to manned spaceflight with a daring mission would remind the Soviet people what their socialist system could do.

Some engineers wanted to play it safe and continue with unmanned testing until all the bugs were worked out, but more unmanned testing lengthened the time since the last manned flight, and Brezhnev wanted to get Soviets back in space. The leader chose a date close to May 1 so the mission would coincide with the National Day of Worker Solidarity. A return to manned spaceflight with a daring mission would remind the Soviet people what their socialist system could do.

It was Dmitry Ustinov, a member of the politburo, who set the final launch date and pressured Mishin to launch on time. He also put immense pressure on Komarov to fly; he threatened to strip the cosmonaut of all his military honours if he refused. (Brezhnev. Source: German Federal Archive.)

Komarov had reason to be wary of the flight. There were known flaws in the spacecraft and general doubt about its readiness to fly at all. Victor Yevsikov, an engineer on the Soyuz development team, knew the spacecraft wasn’t completely ready. But political pressures weighed heaviest and the spacecraft was cleared to fly despite Mishin’s refusal to sign off on the descent module’s flight worthiness.

The engineers weren’t the only ones uncomfortable with the state of the Soyuz spacecraft. There were 203 known flaws in the spacecraft just weeks before launch, and a group of cosmonauts and engineers put together a ten page report outlining all of them. But getting the report into the right hands was a separate issue. The Soviet system had a tendency to blame, and punish, the messenger. (Gagarin, right, and Komarov.)

The engineers weren’t the only ones uncomfortable with the state of the Soyuz spacecraft. There were 203 known flaws in the spacecraft just weeks before launch, and a group of cosmonauts and engineers put together a ten page report outlining all of them. But getting the report into the right hands was a separate issue. The Soviet system had a tendency to blame, and punish, the messenger. (Gagarin, right, and Komarov.)

Days before launch, Venyamin Russayev, Yuri Gagarin’s KGB escort and close friend, accepted the task. After dinning with Komarov and his wife one night, Russayev learned of the seriousness of the situation. As Komarov walked Russayev to the door at the end of the evening, he turned to the KGB officer and said plainly “I’m not going to make it back from this flight.” Komarov explained that he had no choice but to fly. If he refused Gagarin would go in his place. He couldn’t send a close friend and national hero to his death.

Russayev passed the report along, but nothing came of it except that Russayev was banned from interacting with the cosmonauts or anyone affiliated with the space program. He hadn’t even read the document.

The atmosphere was tense on the morning of April 23. Members of the press recalled that Yuri Gagarin seemed particularly agitated. He wasn’t supposed to suit up and go to the launch pad with Komarov, but he demanded a pressure suit regardless. This was a strange request since the nature of Komarov’s flight was such that he wasn’t required to wear a pressure suit. His spacecraft had an airlock through which spacewalking cosmonauts would transfer to Soyuz 1. (Komarov in training. Source: Science Photo Library.)

Many speculated on his actions. Some have suggested Gagarin was attempting to elbow his way in to the cockpit in an attempt to save his friend’s life. Others suggested Gagarin’s demand was an attempt to get officials to put Komarov in a suit as well. It wasn’t much, but it was an added defense against the dangers of the mission. Another suggestion is that Gagarin was just trying to disrupt launch procedures enough to cancel the mission.

Soyuz 1

Komarov launched at 3:35 the morning of April 23, 1967; Soyuz 2 stood ready to launch the next morning. After 540 seconds, the spacecraft had separated from its launch vehicle and achieved orbit. Boris Chertok and his team on the ground took over control of the mission.

Soyuz 1 ran into problems almost immediately when one of the solar panel failed to deploy. The spacecraft was crippled, limping along with half the necessary power supply. Komarov tried to manually deploy the panels. He even tried kicking the spacecraft where the panel connected on the outside, but his attempts to dislodge it were in vain. To make matters worse, the stuck panel affected his guidance system; it blocked the stellar and solar instruments, stopping the cover from coming off at all. By his second orbit, Komarov’s was having trouble with his attitude control, spin stabilization, and engine firing. (A modern Soyuz launch.)

Soyuz 1 ran into problems almost immediately when one of the solar panel failed to deploy. The spacecraft was crippled, limping along with half the necessary power supply. Komarov tried to manually deploy the panels. He even tried kicking the spacecraft where the panel connected on the outside, but his attempts to dislodge it were in vain. To make matters worse, the stuck panel affected his guidance system; it blocked the stellar and solar instruments, stopping the cover from coming off at all. By his second orbit, Komarov’s was having trouble with his attitude control, spin stabilization, and engine firing. (A modern Soyuz launch.)

Chertok and his team set to work finding a solution to Komarov’s mounting problems right away, hoping to work something out while his batteries still had power. It became clear before long that the best bet was to bring Komarov home as quickly as possible.

By 10.00 am, the situation aboard Soyuz 1 was so bad that the launch of Soyuz 2 was cancelled, though some accounts blame Soyuz 2’s cancellation on adverse weather. Around the same time, engineers on the ground developed a plan to bring Komarov down on his 17th orbit with backup options on orbits 18 and 19, well before the batteries would die.

The procedure had Komarov manually align the spacecraft for retrofire, burn his engine for 150 seconds, then try to hold his attitude during reentry. It wasn’t something he was trained for, but he was more than competent enough to pull it off.

The procedure had Komarov manually align the spacecraft for retrofire, burn his engine for 150 seconds, then try to hold his attitude during reentry. It wasn’t something he was trained for, but he was more than competent enough to pull it off.

Falling to Earth

A little before 6:20 the morning of April 24, Komarov burned his retrofire engine. He briefly got his spacecraft oriented, but couldn’t hold his attitude. He reported a retrofire burn, but a failure command in the computer shut the engines off prematurely. From the ground, telemetry confirmed that the descent module had separated from the instrument module and that he was going to land off target. (Right, Komarov in a pressure suit training for Soyuz 1. Source: ITAR-TASS courtesy of Sovfoto.)

But a long landing wasn’t Komarov’s only problem. With only one solar panel deployed, the spacecraft was asymmetrical and its centre of gravity of off balance. As he entered the atmosphere, the Soyuz started spinning, and it only got worse as the atmosphere thickened. Since he couldn’t control his orientation, he couldn’t negate the spin, which meant he couldn’t take advantage of the spacecraft’s aerodynamic capability. He wasn’t generating any lift. He was just falling.

In the United States, the American National Security Agency was monitoring the mission and heard the final minutes of the flight. Chairman of the Council of Ministers Alexei Kosygin spoke to Komarov on a video conference; he cried as he told the cosmonaut he was a hero. Komarov’s wife then came on the line and the couple spoke about his affairs and said goodbye. By the end of the conversation, Komarov’s voice started to show signs of panic. Despite the Cold War, the American’s listening couldn’t help but feel sad — they’d been tracking the cosmonauts for years and felt as if they knew them personally. (Komarov after training in a simulator. Source: Ria Novosti/Science Photo Library.)

In the United States, the American National Security Agency was monitoring the mission and heard the final minutes of the flight. Chairman of the Council of Ministers Alexei Kosygin spoke to Komarov on a video conference; he cried as he told the cosmonaut he was a hero. Komarov’s wife then came on the line and the couple spoke about his affairs and said goodbye. By the end of the conversation, Komarov’s voice started to show signs of panic. Despite the Cold War, the American’s listening couldn’t help but feel sad — they’d been tracking the cosmonauts for years and felt as if they knew them personally. (Komarov after training in a simulator. Source: Ria Novosti/Science Photo Library.)

The final transmission from the spacecraft committed Komarov’s yells of frustration and rage as he plunged to Earth, knowing full well he had no chance of survival.

Soyuz 1 hit the ground at full speed with the force of a 2.8 ton meteorite, flattening the capsule instantly. The force of the impact triggered the retrorockets that were supposed to fire before landing. Instead, they lit the remains of the spacecraft on fire.

Recovery forces in a helicopter sent a flare into the air above the site to signal the location to any nearby recovery crews. The flares they used were colour coded, but without a flare to signify “dead cosmonaut,” they launched one that meant “cosmonaut needs urgent medical attention” over the site of the crash. (The Soyuz 1 crash site.)

Recovery forces in a helicopter sent a flare into the air above the site to signal the location to any nearby recovery crews. The flares they used were colour coded, but without a flare to signify “dead cosmonaut,” they launched one that meant “cosmonaut needs urgent medical attention” over the site of the crash. (The Soyuz 1 crash site.)

Once recovery crews reached the scene, efforts began to save the cosmonaut. Fire extinguishers were ineffective, so men began shoveling dirt over the fire to quench the flames, but the charred spacecraft collapsed under the weight to become little more than a mound of earth with a hatch sticking out of the top.

Immediately, the men reversed their efforts and began uncovering the spacecraft to reach the man still inside. When they cleared enough earth to open the hatch, they found Komarov’s remains still in the Soyuz’s central seat with his headset was still snuggly over his ears. (The burning remains of Komarov’s Soyuz 1.)

Immediately, the men reversed their efforts and began uncovering the spacecraft to reach the man still inside. When they cleared enough earth to open the hatch, they found Komarov’s remains still in the Soyuz’s central seat with his headset was still snuggly over his ears. (The burning remains of Komarov’s Soyuz 1.)

Aftermath

Komarov’s death was formally attributed to multiple injuries sustained by the skull, spinal cord, and bones. The press release announcing his death made no mention of the crash landing that had led to those injuries.

The post-flight investigation focused on the parachute; its failure was the only possible cause of a fatal crash landing. During descent, a smaller braking parachute deployed first. When it was fully inflated it would pull the larger main chute from its casing. Then, just feet above the ground, retrorockets would fire for a soft touchdown. (Gagarin and Komarov in training for Soyuz 1. Source: RKK Energia.)

The post-flight investigation focused on the parachute; its failure was the only possible cause of a fatal crash landing. During descent, a smaller braking parachute deployed first. When it was fully inflated it would pull the larger main chute from its casing. Then, just feet above the ground, retrorockets would fire for a soft touchdown. (Gagarin and Komarov in training for Soyuz 1. Source: RKK Energia.)

It became clear right away that the main chute never deployed, but why remained a mystery. The chutes had deployed flawlessly in testing, both full scale drop tests and static test of the release mechanism. Why did it fail in the mission?

One often circulated story blamed improper packing. The story goes that the parachute was too large for the canister that held it. Instead of being packed tightly, it was hammered into place. When it came time to unfurl, it was stuck and never released.

Boris Chertok had a different theory. In his memoirs, he explained that the Soyuz spacecraft were covered in a thermal protectant polymer, a glue-like substance that was sealed onto the vehicle in an autoclave. When Komarov’s spacecraft was put in the autoclave, the parachute pack was uncovered — this one piece of the assembly was unfinished. The polymer could have easily seeped into the open parachute pack, gluing the chute closed. The test spacecraft weren’t put through the autoclave, so this problem wouldn’t have developed during testing. (Komarov’s state funeral.)

Boris Chertok had a different theory. In his memoirs, he explained that the Soyuz spacecraft were covered in a thermal protectant polymer, a glue-like substance that was sealed onto the vehicle in an autoclave. When Komarov’s spacecraft was put in the autoclave, the parachute pack was uncovered — this one piece of the assembly was unfinished. The polymer could have easily seeped into the open parachute pack, gluing the chute closed. The test spacecraft weren’t put through the autoclave, so this problem wouldn’t have developed during testing. (Komarov’s state funeral.)

The formal recommendations after the flight was to change to shape of the parachute pack from a cylinder to a cone, increase its volume, polish the internal walls for less friction, and to take step by step photo records of the chute installation progress to verify its installation. Development of a better emergency separation mechanism for the backup chute was also on the list of improvement.

Whether a functioning parachute would have saved Komarov’s life is unclear. True to Soviet secrecy, most of the facts about the mission have been pieced together only recently, and Chertok’s version of events has been contested by engineers. There were certainly other problems with the Soyuz spacecraft since the 203 flaws identified by cosmonauts and engineers were enough to convince Komarov he wouldn’t make it back alive. (The open casket at the state funeral show Komarov’s charred remains. Russayev said that the largest intact bone was a heel.)

Whether a functioning parachute would have saved Komarov’s life is unclear. True to Soviet secrecy, most of the facts about the mission have been pieced together only recently, and Chertok’s version of events has been contested by engineers. There were certainly other problems with the Soyuz spacecraft since the 203 flaws identified by cosmonauts and engineers were enough to convince Komarov he wouldn’t make it back alive. (The open casket at the state funeral show Komarov’s charred remains. Russayev said that the largest intact bone was a heel.)

The modern Soyuz reflects decades of improvement over this original model. Every version becomes slightly safer and more reliable. Still, the retrorockets do fail and astronauts and cosmonauts are sometimes subjected to hard landings, but parachute deployment has become more reliable since Komarov’s fateful flight.

Suggested Reading:

Piers Bizony and Jamie Doran. Starman. 1998.

Asif Siddiqi. Sputnik and the Soviet Space Challenge and The Soviet Space Race with Apollo. 2003.

Colin Burgess and Rex Hall. The First Soviet Cosmonaut Team. 2009.

Rex Hall and David Shayler. The Rocket Men: Vostok & Voskhod, the First Soviet Manned Spaceflights. 2001

No comments:

Post a Comment