Note worthy: what is the meaning of money?

As writers and artists invent currencies fit for the modern world, David Graeber reflects on the meaning of money

What would you put on a banknote for our times?

David Graeber

guardian.co.uk, Friday 16 December 2011 22.55 GMT

Article history

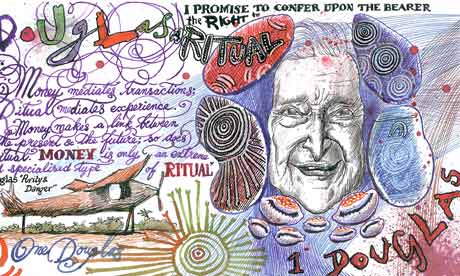

Detail from an alternative banknote conceived by Will Self and drawn by Martin Rowson

=================================================

It affects every aspect of our lives, is often said to be the root of all evil, and the analysis of the world that it makes possible – what we call "the economy" – is so important to us that economists have become the high priests of our society. Yet, oddly, there is absolutely no consensus among economists about what money really is.

Some see it primarily as a commodity traded against other commodities, others as a promise, an IOU, and still others as a government edict, or a kind of ration coupon. Most see it as a kind of chaotic amalgam of all of these. Economics textbooks, whose aim is to reassure us that everything is under control, boil money down to three things: it's a "medium of exchange", a "measure of value" and a "store of value". The problem here, though, is that economists cannot agree on the meaning of "value" either.

Perhaps this isn't that surprising. If economists are high priests, then isn't it the role of the priest to preside over some fundamental mystery? No system of unquestioning authority can really work unless there's something at the core of it that nobody could possibly understand. The effectiveness of this approach can be measured by how difficult it is for critics of the current economic system to come up with a convincing alternative. This is crucial because those defending capitalism have long since given up arguing that it is a particularly good economic system, in the sense of one that has any possibility of creating widespread human happiness, security, or even broadly shared prosperity. The only argument they have left is that any other system would be even worse, or, increasingly, that no other system would even be possible. The challenge is always: tell us exactly how a different system would work. This is especially difficult when we don't even know how this one works. (Had anyone tried to explain contemporary capitalism to anyone who had never experienced it, they would never imagine it could possibly work either.)

Money has always been a particular problem for revolutionaries and anti-capitalists. What will money look like "after the revolution"? How will it function? Will it exist at all? It's hard to answer the question if you don't know what money actually is. Proposing to eliminate it entirely seems utopian and naïve. Suggesting money will still exist sounds as though one is admitting to the inevitability of some kind of market. The actual experience of revolutionary experiments is confusing – no state socialist regime even attempted to eliminate money (aside from Pol Pot's Cambodia, a decidedly uninspiring exception); none, in fact, even attempted to eliminate wage labour.

In a way that's not surprising. For Karl Marx, money ultimately represented the value of human labour, of those energies through which we create the world. It was a way of measuring and parcelling it out, though, in the process, allowing those who controlled the resources to play all sorts of tricks and games. Since socialist systems insisted that labour was indeed sacred and the source of all value, it would have been hard for them to simply stop paying people for their work. The usual idea was to keep the money, just remove the games. Even most experimental money systems such as "Local Exchanging Trading Systems" (Lets), orthe Argentine trueque system follow the same principle: the chits, whether physical or electronic, represent hours of labour, and various means are introduced to make it impossible to play the system for profit: by allowing interest-free credits, for example, or ensuring the chits expire after a set time so they can't be hoarded or manipulated.

But there's no need to start from labour. Money could equally be conceived as a ration chit. Here's a coupon redeemable for so many loaves; here's one for butter; here's one that can be traded for anything. This has very different implications. What they're calling a "free market" turns out to be one where everything is rationed. It's probably impossible to imagine a society where nothing is rationed, but wouldn't we want to keep it to a minimum? So we'd really want to limit the money sphere: perhaps make basic necessities freely available, and provide coupons for the more whimsical stuff, so people can play whatever games they like with chits without getting themselves in serious trouble. Or maybe, better, lots of different sorts of coupons.

But who would issue these? Some central authority? That's the next problem. After all, another definition of money is an IOU, a promise – money is just the way we produce promises that can be precisely quantified and therefore passed around. But who gets to make such promises? In the current system it's not the government but banks – central banks such as the US Federal Reserve or Bank of England. Ultimately the whole contraption is supposed to be authorised by something called "the people". And the authority to make up money does come from all of us, but we're also not really supposed to understand how it all works, so as to ensure that we continue to treat debts we owe in this money that we just authorised bankers to magic into being as sacred obligations, on which no decent person could ever default. So then the question is: once we get wise and blow up all the banks, who gets to make such promises? Everybody?

It's not unprecedented. There was a time, even in England, when most cash took the form of tokens issued by shopkeepers, tradesmen, even widows who did odd jobs. And in a truly free society, who could stop someone from making up any sort of chit or coupon they wanted to? In some Chinese towns, mahjong tokens used to operate as change in markets. Why not? They were always acceptable at the local casino.

People will always play games. Some will involve saying 12 of this is worth five of that, and once you say that, you've got a form of money. Perhaps the best solution would be to ensure everyone has the freedom to create whatever sort of game they fancy, which would probably mean an endless proliferation of types of money, but also that the losers will still never want for feather pillows and something nice to eat.

• David Graeber is the author of Toward an Anthropological Theory of Value (Palgrave Macmillan)

What would you put on a banknote for our times?

David Graeber

guardian.co.uk, Friday 16 December 2011 22.55 GMT

Article history

Detail from an alternative banknote conceived by Will Self and drawn by Martin Rowson

=================================================

It affects every aspect of our lives, is often said to be the root of all evil, and the analysis of the world that it makes possible – what we call "the economy" – is so important to us that economists have become the high priests of our society. Yet, oddly, there is absolutely no consensus among economists about what money really is.

Some see it primarily as a commodity traded against other commodities, others as a promise, an IOU, and still others as a government edict, or a kind of ration coupon. Most see it as a kind of chaotic amalgam of all of these. Economics textbooks, whose aim is to reassure us that everything is under control, boil money down to three things: it's a "medium of exchange", a "measure of value" and a "store of value". The problem here, though, is that economists cannot agree on the meaning of "value" either.

Perhaps this isn't that surprising. If economists are high priests, then isn't it the role of the priest to preside over some fundamental mystery? No system of unquestioning authority can really work unless there's something at the core of it that nobody could possibly understand. The effectiveness of this approach can be measured by how difficult it is for critics of the current economic system to come up with a convincing alternative. This is crucial because those defending capitalism have long since given up arguing that it is a particularly good economic system, in the sense of one that has any possibility of creating widespread human happiness, security, or even broadly shared prosperity. The only argument they have left is that any other system would be even worse, or, increasingly, that no other system would even be possible. The challenge is always: tell us exactly how a different system would work. This is especially difficult when we don't even know how this one works. (Had anyone tried to explain contemporary capitalism to anyone who had never experienced it, they would never imagine it could possibly work either.)

Money has always been a particular problem for revolutionaries and anti-capitalists. What will money look like "after the revolution"? How will it function? Will it exist at all? It's hard to answer the question if you don't know what money actually is. Proposing to eliminate it entirely seems utopian and naïve. Suggesting money will still exist sounds as though one is admitting to the inevitability of some kind of market. The actual experience of revolutionary experiments is confusing – no state socialist regime even attempted to eliminate money (aside from Pol Pot's Cambodia, a decidedly uninspiring exception); none, in fact, even attempted to eliminate wage labour.

In a way that's not surprising. For Karl Marx, money ultimately represented the value of human labour, of those energies through which we create the world. It was a way of measuring and parcelling it out, though, in the process, allowing those who controlled the resources to play all sorts of tricks and games. Since socialist systems insisted that labour was indeed sacred and the source of all value, it would have been hard for them to simply stop paying people for their work. The usual idea was to keep the money, just remove the games. Even most experimental money systems such as "Local Exchanging Trading Systems" (Lets), orthe Argentine trueque system follow the same principle: the chits, whether physical or electronic, represent hours of labour, and various means are introduced to make it impossible to play the system for profit: by allowing interest-free credits, for example, or ensuring the chits expire after a set time so they can't be hoarded or manipulated.

But there's no need to start from labour. Money could equally be conceived as a ration chit. Here's a coupon redeemable for so many loaves; here's one for butter; here's one that can be traded for anything. This has very different implications. What they're calling a "free market" turns out to be one where everything is rationed. It's probably impossible to imagine a society where nothing is rationed, but wouldn't we want to keep it to a minimum? So we'd really want to limit the money sphere: perhaps make basic necessities freely available, and provide coupons for the more whimsical stuff, so people can play whatever games they like with chits without getting themselves in serious trouble. Or maybe, better, lots of different sorts of coupons.

But who would issue these? Some central authority? That's the next problem. After all, another definition of money is an IOU, a promise – money is just the way we produce promises that can be precisely quantified and therefore passed around. But who gets to make such promises? In the current system it's not the government but banks – central banks such as the US Federal Reserve or Bank of England. Ultimately the whole contraption is supposed to be authorised by something called "the people". And the authority to make up money does come from all of us, but we're also not really supposed to understand how it all works, so as to ensure that we continue to treat debts we owe in this money that we just authorised bankers to magic into being as sacred obligations, on which no decent person could ever default. So then the question is: once we get wise and blow up all the banks, who gets to make such promises? Everybody?

It's not unprecedented. There was a time, even in England, when most cash took the form of tokens issued by shopkeepers, tradesmen, even widows who did odd jobs. And in a truly free society, who could stop someone from making up any sort of chit or coupon they wanted to? In some Chinese towns, mahjong tokens used to operate as change in markets. Why not? They were always acceptable at the local casino.

People will always play games. Some will involve saying 12 of this is worth five of that, and once you say that, you've got a form of money. Perhaps the best solution would be to ensure everyone has the freedom to create whatever sort of game they fancy, which would probably mean an endless proliferation of types of money, but also that the losers will still never want for feather pillows and something nice to eat.

• David Graeber is the author of Toward an Anthropological Theory of Value (Palgrave Macmillan)

============================================

No comments:

Post a Comment